Plat was just coming inside from fetching firewood when the orange tomcat ran in through the open door. The animal darted in around his feet, soft and silent as a shadow, and settled by the fire, paws lined up neatly.

Plat stared at the cat a moment before knocking the snow off his boots and closing the door against the winter night. “What are you doing?” he asked, though it was already obvious. The cat was moving in. Plat sighed, recognizing the inevitable, and moved to dump the firewood into the box. “Well, luckily for you, I need a cat around the place,” he said to the basking feline, “but I’m a poor man and can feed no useless mouths. You need to earn your keep and kill the mice. Understand?”

The cat turned to face him. Plat could have sworn the animal inclined his head and let out a mew of assent. Then he returned to his contemplation of the fire and its warmth. Plat went to take his coat off.

For the next week, all proceeded as agreed between man and cat. True, Plat never saw his new cat during the fleeting daylight hours; and when he did see the cat by night, he always seemed to be asleep by the fire, snoring without a care. But there were no more mice or rats around Plat’s hut, so he supposed the cat was doing his job. Plat repaid the cat with bowls of bread and milk and got on with his work, doing odd jobs around Lyng, the village huddled at the foot of the brooding troll-hill of Bröndhöi.

A snowstorm was blowing off the peak of Bröndhöi late one evening, a week after the cat’s arrival. Plat was sitting in his chair by the fire, whittling a spoon, while the cat lay purring in his lap. A sliver of shaving fell on the cat’s smooth orange back, and Plat brushed it away with a laugh. “Wouldn’t do to mess up that fine coat of yours, would it, my boy?” The cat purred in agreement.

Thud. Thud. Thud.

The sound of banging on the door. The cat came alert, ears pricked, back arched, fur standing on end. Thud. Thud. Thud. The cat hissed and darted away, disappearing behind the wood box.

Thud! Thud! Thud! The banging sounded louder and angrier now. Setting aside his tools, Plat hurried to open the door.

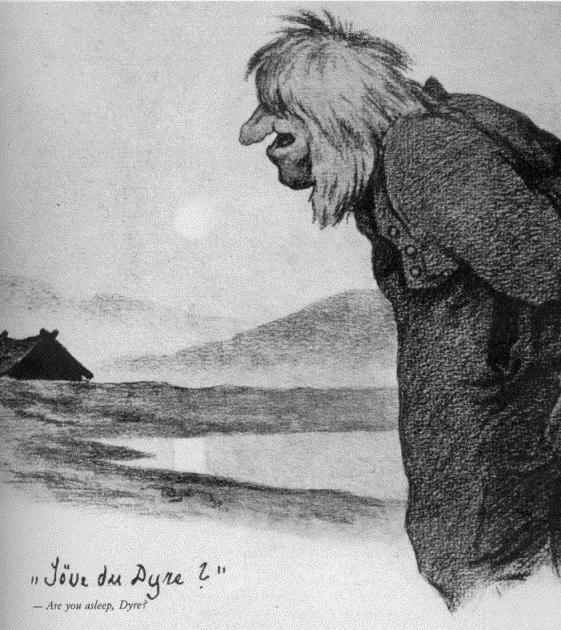

It was no friendly caller. It wasn’t even a human. A troll stood in Plat’s doorway, like a piece of Bröndhöi brought to life, his stony face patched with lichen, his beard green with moss. His eyes glowed with the sullen fires of the earth. He filled the doorway completely, looming over Plat like a thundercloud. The human man gulped, backing away a step. “God aften, herre.”

“Cut the nonsense, mortal.” The troll’s voice sounded like boulders rumbling down the throat of a cavern. “I am Knurremurre, oldest and greatest of the trolls of Bröndhöi. My arm is an oaken timber, my fist cracks boulders. When I walk the forests of Bröndhöi, the trees tremble at my coming.” Knurremurre loomed even higher over Plat. “And some despicable young swine of a troll has been playing around with my wife, Sigyn. I swore I would have his head but, like a coward, he has fled into the human world in disguise. Seen him anywhere, mortal?”

“Y-you’re the first troll I’ve ever seen in my life, good Knurremurre,” Plat stammered.

“Are you truly this stupid, mortal?” Knurremurre unhooked a great club from his belt and tapped it against the door frame. The whole house vibrated. “I said he was in disguise. Seen any strange animals around your disgusting little village lately?”

Plat immediately thought of the orange cat, still cowering behind the wood box. “No, good Knurremurre.”

“Are you sure?” Knurremurre crowded into the doorway, eyes burning like coals.

“Quite sure, herre.”

Knurremurre glowered a moment longer. “Very well,” he growled. “I will continue my search. And if I find you’ve been lying to me, mortal … you will live just long enough to regret it deeply. Understand?”

Plat gave a jittery nod. “Yes, good Knurremurre.”

Knurremurre grunted. With one final glare, he turned from the doorway, a piece of mountain given animation, and thumped off down the nighttime street.

Plat watched him go, until the troll was around the corner and out of sight. Only then did he close the door and shoot the bolt, leaning against the solid wood with a sigh of relief. He was shaking, he realized, cold sweat beading on his forehead.

There came a soft mew. The orange cat stole out from behind the wood box, regarding Plat with nervous eyes.

“Well,” said Plat when he could finally speak, “it seems we are to keep faith with one another, good sir cat.”

***

Knurremurre did not reappear, not during the Jul celebrations or the long, dark days of winter that followed. Plat’s house had never been so free of vermin, even though he never saw the orange cat in daylight and the animal spent the long, dark evenings curled up purring in Plat’s lap. The human man stayed close to the village that winter and kept an eye out for trolls. However, he saw no sign of Knurremurre or any of his people, not even the disputed troll-wife.

Sometimes, on clear moonlit nights, Plat thought he heard music flowing down from Bröndhöi: a woman’s voice, thin as a silver thread, faint as starlight, full of sadness and longing. On those nights, the orange cat did not sit in Plat’s lap. He sat in the window, staring out at the unreachable hill, ears pricked to catch every note.

Winter finally gave way to spring, the snow melting in rivulets, the village streets turning to marsh. Plat saw the cat less as the days lengthened. He ventured further afield, reassured by the knowledge that even the strongest troll must revert to stone to weather the daylight hours. During the endless summer days, the sun barely dipped behind Bröndhöi, and Plat gathered and foraged in the deep green forests, wondering if every boulder he passed was a sleeping troll. But as summer advanced, its light and warmth seeming endless, Plat slowly relaxed, telling himself he was unlikely to see Knurremurre or any of his kin.

In this, he was mistaken. On the first day of autumn, when the winds carried tastes of frost and the sun had truly set, Plat found himself delayed getting home. He hurried back along the forest paths, his basket heavy on his back, cursing himself for not paying closer attention, while around him the shadows of the forest night deepened. He was just walking past a lichen-stained boulder when it stirred, stretched its limbs, and stood up to reveal itself a sleepy-eyed troll.

Plat leapt back with a strangled cry, mind flying instantly to Knurremurre. But this was not he. Instead, a troll-woman stood before him, brushing leaves and fern fronds off her dress, her eyes like silver stars. She focused those eyes on him and said warmly, “Hello, Plat.”

Instantly, Plat knew this was the singer from the hill. Her voice was silver thread and starlight. “God aften, frue,” he said, bowing. “How do you know my name?”

“Oh, I know a lot about you, Plat,” said the troll-woman, still warm and unthreatening. “I’m Sigyn, lately the wife of Knurremurre.”

“An honor to meet you, frue,” said Plat, marveling at finally meeting Knurremurre’s straying wife. He supposed he could understand what the younger troll saw in her: she was clearly a beauty of her kind, her rock-skin smooth, her eyes glowing with silver fires, her moss-stained hair long and smooth.

Sigyn laughed in delight, like cold water flowing over rocks. “Your manners are excellent, Plat! No surprise, of course: you’ve kept faith with a troll, all these months, and so a troll will keep faith with you. I have one last favor to ask of you.” She leaned in, cold scent of rocks and water and moss breathing off her. “Go back to Lyng,” she said, “and tell your cat that Knurremurre is dead.”

“He is?” Plat exclaimed in surprise and relief.

“He is,” Sigyn confirmed. “Go tell your cat that Knurremurre is dead and it is safe for him to return to Bröndhöi.” A luminous smile lit her face, like flowers growing across a rock. “Indeed, we eagerly await his return.”

“That I’ll do, frue, with a goodwill!” cried Plat, and, bowing once again, made his way down the path out of the forest and back to Lyng.

The cat was waiting for him on the front step, furry face raised. Plat, breathing hard from his run down the hill, grinned. “I have excellent news, cat,” he said. “I met Sigyn in the forest. Knurremurre is dead, and it’s safe for you to return home!”

For a moment, the orange cat sat still, as though not daring to believe what he had just heard. Then, with a yowl of joy, he stood up on his back legs, like a small, furry gentleman. “Well!” the troll-turned-cat declared. “Then I must go home as fast as I can. Sigyn is waiting!”

And he ran out the door and down the street, already smoothing his fur back with one paw.

Plat watched him go. Then, with a shake of his head and a little laugh, he took his basket inside his hut.

***

But that was not the last encounter Plat had with troll-kind.

Three days later, before anyone else in the village awoke, Plat opened his door onto a chilly dawn and a large, heavy object sitting on his doorstep. It was a leather bag, drawstrings tied shut, contents bulging.

Squatting down, Plat opened the bag, loosening the strings. The contents gleamed in the early morning light.

Gold coins. Hundreds of pure gold coins, glinting in the leather bag.

A scrap of white was tied to the purse’s laces. With trembling fingers, Plat disentangled the birchbark paper and unrolled it. On it, in spiky letters, was written:

Keep faith with a troll, and a troll will keep faith with you.

[Rose Strickman is a speculative fiction writer living in Seattle, Washington. Her work has appeared over 70 times, in anthologies such as Sword and Sorceress 32, Beneath the Yellow Lights and Wild Hearts, as well as several e-zines such as Translunar Travelers Loungeand Eternal Haunted Summer. Her novella Island of the Drowned was published as a standalone title by Graveside Press and she has self-published several novellas on Amazon. Please see her Amazon author’s page at https://www.amazon.com/author/rosestrickman or connect on BlueSky @rosestrickman.bsky.social.]