Coming forward is a big step for you. I know you’re uncomfortable, I know that. I’d like to help you with your discomfort with owning what happened to you, and to let you know there’s someone who can help—that this is fate, divine intervention if you will. The first time I met her, she was wearing overalls with little flowers and gnomes on them. It’s not what I expected, I mean, it wasn’t what I expected once I knew she was a sorceress.

When I met her the first time, it seemed right. She was a woman in farming, an ag sciences legend. America’s Pig Farmer of the Year from the National Pork Board. The next “Jan,” meaning the next Jan Stanford, past president, and first female president of the National Pork Board. An advocate for women in agricultural spaces. She wasn’t like a lot of the other women, though. No husband, no “mom of three” or “proud grandmother” in the articles about her. She didn’t talk about being raised on a farm, or 4H, about a family history of farming in Iowa or Oklahoma or North Carolina or any of the places people thought she was from but could not quite pinpoint, and that they’d promptly forget to ask about the next time they saw her.

Later, they’d always say they were struck by her beauty. Then, quickly, they’d say it was her intelligence and passion for livestock husbandry and Pork Quality Assurance®. I was starstruck by Ms. Katsaros. She’d started the Women’s Ag Society when she was a student, back when there were hardly any women majoring in Ag Sciences, let alone working with the larger animals like cows and pigs. When she came to Nebraska State when I was a sophomore, and planned an extra hour to talk to our chapter, the other girls were excited so I was excited too. We clustered in a classroom for the Q&A, bleary eyed and clutching our Stanleys at 7am.

Most of us had already been to the barns and were caffeinated, but some of us had also been up late the night before, either studying or partying, or a mix of both. I was one of the ones who’d already been to the barns. I’d also already been invited to a party by a boy named Trevor, and even though it was hours away I was already anxious about it. Meeting Ms. Katsaros was a welcome distraction from my paltry social life.

The Q&A was led by Professor Morgan, the faculty advisor for the Women’s Ag Society. She was one of those “became a farmer because I married a farmer” but then took their farm from barely subsistence to thriving and expanding because she took extension courses and then eventually worked her way up to a Masters in Livestock Husbandry. She never talked about her husband, and like a lot of the faculty that worked in the barns, didn’t wear a ring or any other jewelry. I don’t know if she was even still married. Her research and publications, like Ms. Katsaros, was part of the rise of women choosing farming on their own.

“Quiet down, girls,” Professor Morgan waved her hands at us dramatically. Her thick red hair was pulled back into a messy bun, visible pens sticking out from it. She was stunningly beautiful, even in her…40s? 50s? No one really knew, and only boys ever asked. She’d just smile coyly at them and say, “How old do you think?” and then pull a pen from her hair and let it cascade down. She’d flip her hair over her shoulder and go back to whatever she was doing. We’d practice it in our dorm rooms, clumsily imitating her and never quite getting it right. I don’t know if she’d be amused or offended. We worshipped her. And now, another woman worthy of our devotion was sitting with Professor Morgan in the same room and ready to answer our questions.

We were silent almost immediately. Good girls, all of us. Followed instructions. Listened well. Took our studies seriously. Did extracurriculars in high school. Future Farmers of America. 4H. Sang in choir. School or church, depending on whether we were homeschooled or not. Sometimes both. A few girls were in their high school musicals and would break out into song when we were in the barns. The boys made fun, but we knew the animals loved it. The boys loved it too, but wouldn’t just say that.

Ms. Kastaros was as stunning as Professor Morgan. She had thick, dark hair that spilled over her shoulders. There were just a few grays interspersed, which, rather than making her look older, made her face appear more youthful. She had arched eyebrows that didn’t look like she had to painstakingly fill them in daily, like I did. Long eyelashes, full lips. No makeup. The kind of beauty that every girl knows exists, and thinks about when her mother says things like “everyone is beautiful in her own way” and pats your hand, looking away, so you can’t see the lie in her eyes that you’re not beautiful, you’re cute at best, average on most days, and by the time you’re thirty, you’ll have faded to the kind of woman whose name no one can remember minutes later. But not these women. And these women were farmers, not movie stars. Is it any wonder that we were enchanted by them? Even without all the rest?

“Ms. Kastaros, I know the girls have lots of questions for you, and we’re so glad you made some extra time to meet with them. Why don’t you get started by telling us about what the girls need to be successful in pork farming?”

“Please, call me Circe.”

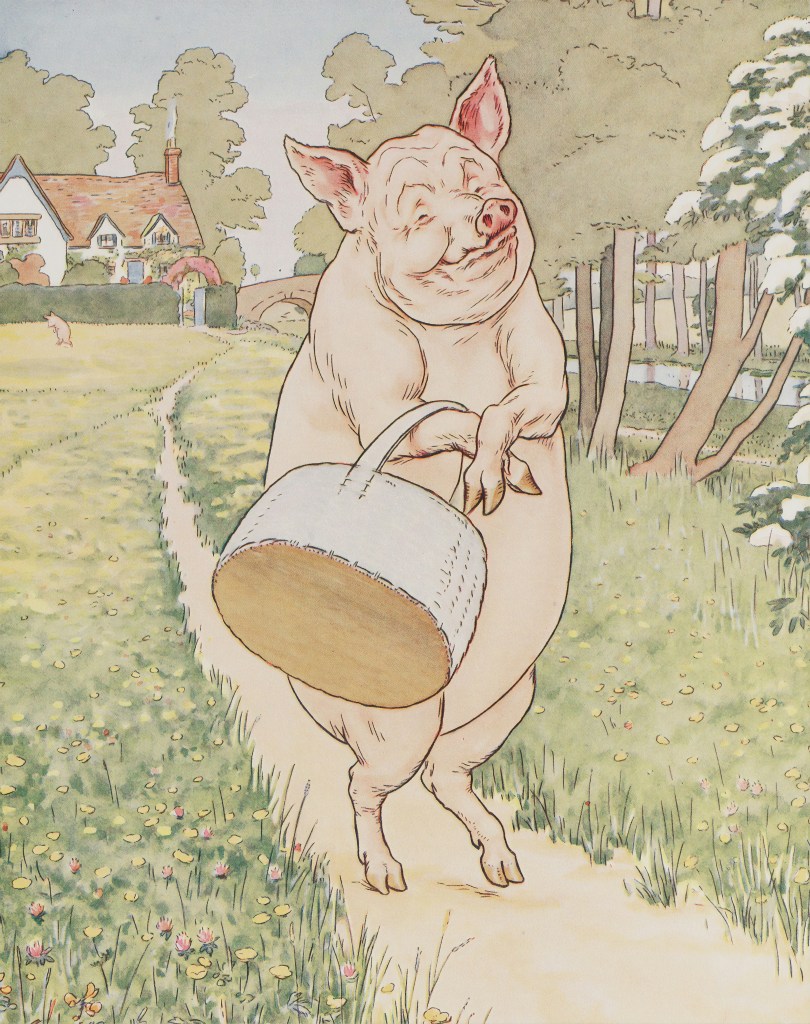

There was a silence, but not really a silence. It was more like a thousand songs and the wind over an island I could see in my head like a memory, but I’d never been out of the Midwest. I’d never seen the ocean, let alone the Adriatic. Not yet, anyway. There was laughter of women, free and easy and unencumbered, and animals, so many animals, everywhere. The pigs were docile in their pens, with dappled sunlight streaming through the trees. It was the most peaceful moment I had ever experienced. I forgot it all immediately, and like all the other girls in the room heard “Siri” like Katie Holmes’ kid or the Apple voice.

“I went into pig farming in large part because pigs are so intelligent. They’re also smaller than cattle, so they’re more manageable. No one gets gored by a barrow.”

Tepid laughter around the room. Barrows are castrated male pigs. They’re the largest portion of the pork market.

“As far as what you need for success, well, like all farming, you have to be committed to ethical principles and sustainability. My farm, Grove Farms, is named for the forest grove that makes up a significant portion of the land. Our pigs fall under the ‘free range’ category, though as you all know, that designation means less than what consumers think it does. They need to root, dig, and forage. It’s in their nature. They just can’t leave well enough alone.”

More laughter. We all lean in, eager for more. Some of us take notes.

“Especially now, with climate change, you also have to think about how to keep your livestock healthy in heat waves. Sows are more vulnerable to heat stress and transport, so we try to keep them as healthy and happy as possible—we use a lot of herbal remedies. We don’t keep many boars. Most pig farms keep only 1-2, and we cycle them out. Barrows are what are mostly sent to market, but we dry age our pork, which means we don’t depend entirely on younger pigs for tenderness of our chops. We take a more holistic approach to our entire farm, and it’s why we have a superior product. It costs more, but it’s worth it, don’t you think? And, if you keep an eye on hog futures, the higher quality meats are less volatile and remain steadier in the market.”

“As you may have heard me say at the Farmers and Ranchers Alliance banquet, where I spoke recently, pork is a quality protein source. I think it’s the best one in the world. It’s the number one protein source in the world. It’s an economical protein, and it makes an enormous difference in people’s lives, from the farm to the grocery store. It is up to us, as women in agriculture, to feed the world.”

We erupted into applause. How could we not? She fed us, not just with high quality pork products, but with the purpose we’d all felt as part of the draw to farming as a livelihood. Even those of us who’d grown up farming adjacent—my parents lived in the suburbs, but my grandparents had a small farm. It wasn’t a working farm, it was a hobby farm. You could see the remnants of what it once had been, and I had dreams of bringing it back to life. Of sustainable living, the cottagecore fantasy of Tiktok homesteaders. But I was going to go into it informed and with a plan to make it—really make it, not go from one financial crisis to another, like my parents in the ‘burbs. Ms. Katsaros sang to us of hope of a life, a real life worth living, and not of one where we’d just be cogs in someone else’s corporate machine. We were all in, before she even stepped into the room. Enchantment wasn’t necessary.

“What are your favorite things about farming?” Asked by a junior, this insipid question was as banal as the voice it came from. Judy was a bland, plump girl from western Nebraska whose window of “beauty” was even shorter than mine. She’d already fallen in with the fundamentalists, where her lack of personality was considered a boon to their way of living. If she stayed in farming, she’d be one that was married to a farmer, would call herself a farmer’s wife instead of a farmer herself, and have a blog of recipes full of spelling errors and canning tips that might end with botulism. She wasn’t careful in her lab work now, and it was unlikely she’d be fastidious with food safety in the future.

But Ms. Katsaros was a total professional. “My favorite times of year are when we get new pigs in, and when we ship the market hogs. Think about what your favorite things are about your work in farming—because there are a lot of tasks you won’t like doing. Men will use that to discredit you.” She maintained unbroken eye contact with Judy. Goosebumps raised on my arms, a sudden chill in the air, a cool breeze from that ancient sea across the island. “We want the right people raising pigs.”

The session ended after more questions about hog futures and working with the National Pork Board, high costs of feed, what to do about bacterial infections, and other practical questions. She told us her staff was almost entirely women. That was new to most of us. Even many of the other women farmers we’d met had mostly male hired hands. Judy asked another stupid question about naming the pigs. Ms. Katsaros told us, laughingly, that she and her largely female staff named the sows after queens and named the hogs destined for market after their ex-boyfriends. “At any given point, we have six or seven Chads or Trevors.”

Her words about the “right people” stayed with me all day. I saw the Trevor who invited me to a party in one of my classes later. That his name was on the “market hog” name list made me smile. I think he assumed the smile was for him. He was handsome-ish. In the same way that I was cute. He’d hit thirty, and then the double chin would set in, and his face would redden, from sun, from anger, from rosacea. He’d still see this version of himself in the mirror somehow, this young, tall, tan version with smooth skin and a winning smile, all-American corn fed white boy who is an important part of his community. This illusion was bred into him early, in sports, in 4H. I knew many of his type, both from home and in college. But what were my other options? I was an ag sciences major at a state school, I wasn’t going to find some brooding poet type wearing a blazer, hair hanging in his eyes who wanted to read Keats to me under a tree on my farm.

A Trevor was my future, and I had to be ok with that. Think about what your favorite things are about your work in farming. Trevor is a task I won’t like doing. Ms. Kastaros—Siri—might talk a good game about women in farming, but I knew my community. I’d need a Trevor if I was going to survive.

That night I wore my best jeans, the “dressy” ones, because in those days I still thought there was a “dressy” option for jeans. A white t-shirt with a v-neck that showed just a little cleavage. I mean, I only had a little, I was working with what was available to me at the time. I wasn’t trying to attract Trevor. Let me be clear on that. I felt like Trevor was just something I’d have to fall into. A sloppy kiss at a party, like the one I was attending. Dating for two years, an engagement senior year. Then we’d move to the farm and start the life I wanted, and I’d tolerate him. That’s what was expected of me. I’d love our daughters, and tolerate the future little Trevors, though I’d love the parts of them that were me, and resent anything they learned from him. I don’t tell you this so you feel sorry for Trevor. You shouldn’t.

I had a red Solo cup of beer that Trevor poured me. He chided me for “nursing” it. I drank more, drank faster. The cup never seemed to be empty. There was beer pong, spills on my white t-shirt, my good jeans. I went to the bathroom to clean myself up. I wanted to throw up. I wanted to go home. I wanted a farm with a grove of trees with a name I hand painted on a sign. I wanted something I could be proud of. I wanted an island full of animals and no men. I wanted my poet-husband. I wanted to be free.

I came out of the bathroom and Trevor was there, leaning against the hallway wall, and blocking the path to the stairs.

“How are you feeling?” He smirked as he said it. “You really can’t hold your alcohol, can you?”

He didn’t care one bit how I was feeling, and, even drunk, I knew it.

“Immagohome.” I slurred my words as I moved toward the stairs.

He stepped in front of me, and grabbed my shoulders.

“Whoa, you really need to lie down.”

It was a blur to his room. That was back in the days when fraternities were allowed to have houses. Things have changed. Well, not as much as we’d like, of course. You’re here, in this office. You told me your story and I’m telling you mine so that you understand that what happened to you is not your fault.

I was on his bed. My white t-shirt was gone. Beer had seeped through to my bra, and in that moment, I was so mad that my good bra was going to be stained. Not for what was happening, his clammy hands all over my body. Trevor was down to his boxers and I prayed. Not to God. To Circe—I no longer thought of her as Ms. Katsaros—I prayed, help me.

What I didn’t know was that she was already there. She was down the hall, rescuing a drugged Judy from another Trevor. Literally, not figuratively. That fraternity had, like, nine Trevors. The door blew open, and a smell of the salt air, of olive oil and slow roasting and wine and rosemary and thyme and night blooming jasmine burst in with her. She was wearing a dark dress, the color of wine I couldn’t afford to drink then. Wine I later learned to make. She wore jewelry, too. Gold bracelets twined around her arms like snakes.

She hissed words at him in a language I was unfamiliar with. Then, at least. He buckled, he shrank, he expanded. Hooves erupted from his palms and a curly tail from his backside. Transmutation was clearly very painful. Even drunk, unable to fully process what had almost happened to me in that room, I was glad. Grateful. Relieved. My savior had come, and I would follow her.

Judy strode in, stone cold sober. I only found out she’d had a glass of Sprite laced with Rohypnol much later. She’d come to the party as the DD for her roommate.

Circe came close to me, looked in my eyes and inhaled, pulling the poison of alcohol out of me. I was as sober as Judy in seconds. Able to find my t-shirt, crumpled on the floor. I put it back on, even though it was smelly and damp. There were two squealing Trevors in the room with us.

“We need to get these pigs to the farm. You girls create a diversion, I will take the pigs out the back.”

Judy and I thundered down the stairs screaming about an infestation of spiders and rats. We should maybe have gotten our story settled before running down the stairs screaming, and picked just one thing, but, hey, we were new to this whole turning our assaulters into pigs thing. Circe didn’t let us down, there were spiders and rats, coming out of the walls, running down the stairs. Later she said Judy and I called forth the spiders, the rats. It was the first time we spoke to the animals and they came to us. We didn’t believe her. Not yet, anyway. The party scattered into the night.

Judy and I met her at the barn later after a wordless drive. Was it just me, or was Judy prettier? Her hair, usually braided to minimize frizz, was down, silky, and smooth. Her cheekbones seemed more prominent. I didn’t glance in a mirror then, I was too hesitant. I’m forty-five, you know. Now. I know I don’t look it. My husband—I did get that poet, by the way, he’s won a lot of awards. Also writes articles for the National Pork Board and edits for the American Hog Farmer. We are still a practical couple, though he does sit under a tree and read me poetry, to this day. Anyway, he always says I’ve not aged a day since we met in graduate school. We do raise pigs on our small farm, even though I work here on campus. Expectations met, in our own way. He knows what I am, too.

It’s ok that most people don’t remember my name, I prefer that. Mostly they refer to my job title, “Title IX Coordinator,” but “Title IX Lady” is just fine. I’m the one you see when something terrible has happened and you need to know your legal rights. And perhaps find your revenge, in one way or another. I’d like you to meet her. Circe, that is. Do you feel the wind? Do you smell the salt air?

You are not special because a man took from you, you are special because you have the potential for enchantment. We are everywhere now. Judy wound up being the “new Jan,” you know. She’s the president of the National Pork Board. Also married. She and her wife have six wonderful children. A sustainable farm. She put a face on pig farming—a human one, a really charming, beautiful face too. So many of the pigs are Trevors. Or, were.

Don’t worry about the missing persons report. Those disappear. Boys like that, like your…Chett, ugh, of course. Boys like Chett disappear, and the cops always tie it to drugs, or deaths of despair. No body is ever found. Well, no human body. And you mustn’t consider eating pork to be problematic. That’s not how transmutation works. They’re pigs, always and forever after they’ve changed, and you can take samples to the biology department if you doubt me. Pork, down to the DNA. We want the right people raising pigs, after all.

[Joanie Brittingham (she/they) is a writer and soprano living in New York City. Brittingham is the Associate Editor for Classical Singer Magazine, the author of Practicing for Singers, and has contributed to many classical music textbooks. Brittingham’s writing has been described as “breathless comedy” and having “real wit” (New York Classical Review). Brittingham is the librettist for the opera Serial Killers and the City, which premiered with Experiments in Opera, and was a part of New Wave Opera’s Night of the Living Opera. Their writing has been included in Black Cat Tales. On Instagram and TikTok: @joaniebrittingham.]