Sing, O Muse, of the handiwork of Eris, Goddess of Discord, and the folly of Hubricretes the Fair; how the city of Athens dripped with sweat, roasting like a sacrificial lamb beneath the blazing white chariot of Helios. Tell how free-men and slaves, nobles and beggars, women and livestock, flowed through the city’s wide, unpaved streets as blood flows through a man’s veins. And of its heartbeat: the constant echoes of their footsteps.

Animal and human voices mingled as one within the bustling agora. Bleating, laughing, bickering. Rumors jumped from ear to ear like hungry lice while merchants haggled from their stalls and rhetors clashed with Sophists on the steps of lofty stoas. Holy invocations laced with rich, ambrosial incense rang out from every temple and rose above the din to high Olympus.

Somewhere in that space beyond the sight of men yet beneath the Twelve Olympians, Eris, dark and terrible, flapped her leathery wings. She scoured the noisy maelstrom far below with impatient, mismatched eyes for every vengeful or ambitious heart, each misremembered slight or jabbing pang of envy; any opportunity to stoke the eager flames of strife.

It did not take her long to find a swirling cloud of jealous rage … so dark against the sunlight …malignant and seductive .…

Down,

down,

down she followed its long, twisting root to the verdant courtyard of a wealthy merchant’s mansion on a hill, amply stocked with every sort of luscious fruit tree, fragrant herb and flower that flourished across the Aegean.

The daughter of the merchant sat cross-legged by a fountain at the center of the courtyard. In her lap, she held a tortoise-shell lyre whose strings she nimbly plucked and strummed with an ivory plectrum. All the plants appeared to sway in time with the lilting rhythm of her notes, the pebbles hovered almost imperceptibly above the soil, and the water spouting from the fountain did twist in strange directions. The young girl’s head was full of beauty and had hardly any room for spite, let alone a vortex.

Eris found the mind that did contain such malice soon enough, skulking in the shadows of the colonnade where he spied upon his sister, Ida, with obvious contempt.

The Goddess of Discord crept into his head and watched jealous thoughts flow by …

How Hubricretes loathed the perfected artfulness and care with which Ida moved her fingers across the strings.

In every other aspect, he knew he was superior to her. He was male, she was female. He was handsome, she was homely. He was fit, she was fat. But in music, he was hopeless. No matter what the instrument, he could never get it right and always gave up quickly from embarrassment. Sweet music seemed to shun him; each note was a battle, and every harmony a war.

But Ida conjured melodies with supernatural ease, as if she were the offspring of a god; how could one compete with that? It was not worth the effort …

Such was the salve Hubricretes compulsively applied to his badly bruised ego. Of course, he had no proof their father was a cuckold and that Ida’s true sire was a god, but it was easier to think so. He prayed Apollo or the Muses would intercede and simply give him the skills that Ida had and more, that way he could truly beat her.

The Goddess of Discord clacked her bony claws. This was oh-so-very wonderful! The kindling was set; all she needed was a matchstick. And she had just the perfect thing .…

She descended swiftly into Tartarus, bounded through the orchards where she grew discordian apples, and leapt into her workshop. By the time she returned to the mansion on the hill, her mother, Nyx, had cast a starry, black pall over Athens. Eris withdrew her claws, bent her body into pleasing curves, rubbed her scales into smooth, alabaster flesh, and covered her wings with a thick, woolen peplos.

Once a monster, now a Muse.

She found Hubricretes dreaming in his bed, then once more she slunk into his head .…

“O Fair Hubricretes,” she declared, standing on the threshold of dreams with her hands behind her back, “Your prayers have not gone unheard by we Muses Nine on Helicon, most holy.”

The golden-haired youth stirred in his sleep. Eris continued, “We too grow weary of your wretched sister’s disregard for your obvious superiority; ‘tis unseemly and unjust. Thus, we have decided now to ameliorate your long-suffering.”

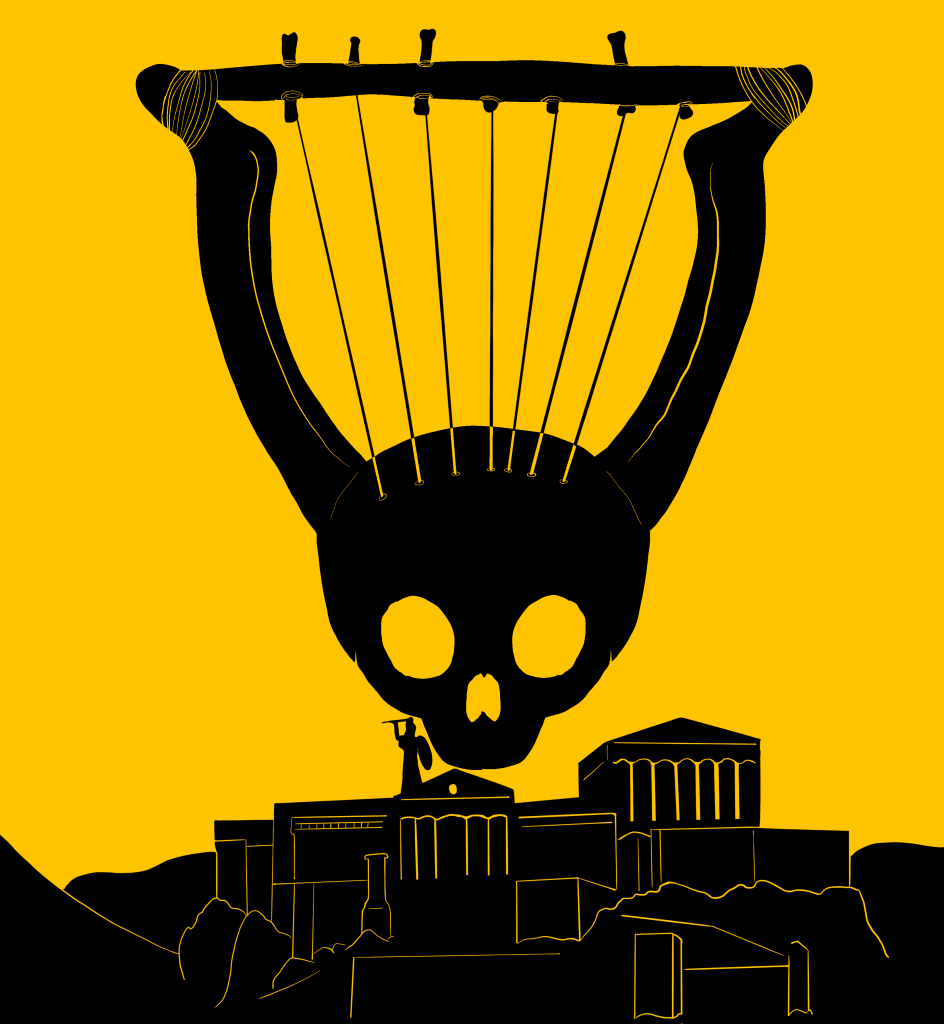

From behind her back she revealed a lyre, blacker than the blackest night. Its strings appeared to move beneath an unseen hand and sweet music filled the room

“Behold! No need to pluck the strings, for they do it to themselves. No need to waste time practicing, for it simply pulls the music out of you.”

Eris paused to place the lyre upon a wooden chest.

“But heed my warning, Golden-Haired Prodigy,” she continued, “The darkness is your friend. Put your bastard-sister in her place; remind her she is lesser-than. But do so only once the sun has set, lest errant eyes see more than they ought … Farewell, Fair Mortal, and good luck!”

Eris faded from his mind, then smiled …

… she knew he would not listen.

The chariot of Helios had resumed its place in the sky when Hubricretes awoke in a gasping panic. Slowly, cautiously, he turned his head towards the wooden chest by the door. The black lyre was still there. He picked it up and held it; he was not sure, but it felt like bone and emitted a faint, smoky odor as though it had been lying in a fire.

But how did it work?

He thought of music, no song in particular, and the strings began to vibrate; ringing and ethereal. His furniture began to dance and float around the room while water from a pitcher spiraled in mandalic configurations.

Hubricretes laughed. This was unbelievable! He would best his sister once again, and soon all the world would stand in awe of him, Hubricretes the Fair — Orpheus reborn.

To Hades with caution! He would not obscure himself in the darkness of the night. He wanted to be seen as well as heard. Besides, he could pretend to play it easily enough … could he not?

Eris felt a rush in her feathers as Hubricretes set to work miming finger movements over the black lyre. Then she flew across the City of Reason to whisper in an old man’s ear …

Later that morning, a penniless philosopher discreetly shuffled through the Dipylon gate on filthy, calloused feet, narrowly weaving between steaming piles of excrement as he navigated a tumultuous sea of bodies. His eyes darted first here, then there, searching for pursuers. Frayed hempen rope burrowed into the peeling, terracotta flesh of his chest, supporting a large, wicker basket that he carried everywhere he went. When there were no Sophists left to heckle in the symposia, nor any simple-minded dregs to humiliate in the wine-sodden kapeleia, or even passersby to feed him scraps in the streets, he would find some obscure place, curl up in a feral ball, and sleep beneath this basket.

Whence he earned the moniker, Krassios the Vulgar Tortoise.

Krassios had been dead asleep in the ancient cemetery of Kerameikos just outside the city walls when a familiar voice convinced him, against his better judgement, to go back inside the city from which he had been banished just a day before on pain of death.

Stealthily, he hobbled along the Panathenaic road, across the vast agora, past the sacred Acropolis, and up the hill that was described by that compelling voice inside his dreams. The old iconoclast shouldered his way through an ever-thickening crowd that clotted together like some impenetrable murmuring scab inside the peristyle courtyard of an ostentatious mansion. Krassios scowled and spat yellow phlegm on the mosaic tile floor. He was disgusted by the rich.

After much aggressive prodding, the crowd let him pass to the front, not out of respect, but for the sake of their own nostrils. He watched with disdain as a smug, golden-haired youth, sitting cross-legged on the edge of a fountain, confidently plucked the strings of a lyre, black as midnight.

All the plants in the courtyard danced and swayed in time with the lilting rhythm of the notes, stones rolled in concentric circles and jumped up and down with unnatural slowness, and the water of the fountain danced like a mesmerized serpent. The lyre-player cast frequent, pretentious glances at a slumping young woman standing next to him whose red-rimmed eyes bulged in amazement. She also clutched a lyre against her plump belly.

The crochety rhetor absorbed every detail. His body was old, but his senses were sharp. Something about that lyre-player’s hands was not right … but before he could figure it, the music stopped and was replaced with loud hoots and clapping. The smug musician took a bow.

Krassios’ logical mind urged him not to make a scene, for already he had heard his name whispered in the crowd, but the temptation in his heart to tear down such a pretentious, wealthy brat was more than he could handle. He hobbled forward.

“Pardon me, young man,” he said, employing his warbliest affect, “I much desire to see the technique of such a masterful performer but, alas, my poor eyes are not what they once were. May I stand a little closer and observe? I shan’t interfere.”

The lyre-player hesitated. He looked down at his instrument, then waved a hand in front of Krassios, who took special care not to react.

Satisfied, the lye-player smiled and said, “Of course, honored elder. Observe as long as you wish.”

Krassios gave his thanks and a new song began. Before, the music was majestic and sad, like a wild beast pacing the confines of a cramped menagerie, forced to perform for ugly, jeering patrons. Now it was jaunty, glad and … familiar? Krassios could not place it, but he knew that he knew it.

When he emerged from his revery, he instantly detected that the musician’s finger movements did not align with the sounds the instrument produced.

He aimed his own puffy, arthritic finger in the lyre-player’s face and shouted, “Fraud!”

The music stopped with an abrupt ‘twang’ and the audience gasped. Now it was Hubricretes’ turn to scowl.

“What was that, old-timer?” he asked.

“I said you are a fraud,” said Krassios, “Your clumsy fingers cannot play such music any more than mine.”

Hubricretes scoffed.

“You must really be blind after all!” he hollered, “Did you not see the flowers sway, the stones jump, and the water dance to my music?”

Now Krassios scoffed.

He began bellowing sing-songy gibberish as he sauntered to a bed of flowers, turned his rump against them and broke wind, causing the dainty blossoms to rock and sway. Then he grabbed a handful of pebbles and hurled them in the air, much to the consternation of the crowd. And after that he promptly lifted his loincloth and urinated in a zig-zag pattern, barely missing dozens of sandalled feet. The audience howled at every act, and Hubricretes’ face turned deeper shades of red.

“Behold!” proclaimed Krassios, “My music can do everything yours can!”

“You are a disgusting pig!” cried Hubricretes.

“Perhaps,” said Krassios, “But while you take offense at perfectly natural corporeal processes, I am more concerned with incorporeal offenses such as lying and deceit.”

“So, you really think me a liar, eh?” asked Hubricretes.

“In a sense, yes,” said Krassios, pointing now to the black instrument. “However, this lyre contains inherent musical potential while you possess none.”

Krassios allowed time for the audience to gasp and guffaw before he continued.

“I saw your fingers moving but they did not match the notes, nor did they touch the strings. I do not know how, but your instrument played itself.”

The audience murmured. Hubricretes’ face now had the hue of a ripe tomato.

“You see too much, old man,” he hissed through perfect, gritted teeth.

Krassios cackled. Then he recalled the pouty girl standing next to them and said, “If you wish to prove your skill, liar-player, why not try her lyre instead?”

Hubricretes huffed and puffed.

“No,” was all he said.

Krassios smirked, even as he saw stern-faced guards emerging from the crowd and encircling him. He was not surprised that these dull-eyed hoi oligoi had sold him out. Nor did he complain when his basket was smashed and he was dragged off to prison. But when they grabbed his scrawny arms, the black lyre screeched, and a massive crack splintered the mosaic tiles on the floor.

The trial was swift, and the sentencing savage: for his crimes against the state, including impiety, corruption of the youth and disruption of civil order, Krassios was to be boiled alive in the agora for all to witness.

As he awaited his fate on a sparse pile of hay deep in the desmoterion, he heard music echo through the halls and gentle footsteps scrape across the brick floor. A young girl stepped into the torchlight, strumming a lyre.

Krassios recognized her as the girl from the fountain.

“How did you get past the guards?” he rasped.

“I lulled them to sleep with a song,” said Ida, “Now hurry, it’s nearly dawn. I’ve come to set you free!”

Krassios saw her fiddling with a ring of keys and asked her, “Why?”

Ida smiled at him.

“Because,” she said, “You made a fool of my cruel brother … and I shall cherish that moment always.”

Krassios chuckled, then looked away.

“The black lyre played a familiar song …” he murmured, “I think it played it for me …”

Ida scrunched her face.

“I-I do not understand,” she said.

Krassios cleared his bone-dry throat and told her, “I once loved a bastard son of Apollo … he played that same song for me while we were walking down a road one day … the same day we came across a giant stone … a woman was standing by it … I remember, she had mismatched eyes and wild, black hair. She told us there was treasure underneath the rock, and whoever helped her move it could split the gold with her …

“We were very drunk, and I opted to go first. I tried to move the rock with philosophy and rhetoric, but to no effect … my arguments did nothing. Bastophon went next. He played his lyre … and the music lifted that boulder up as if it were … a pebble.

“The woman gave him his share, as promised, and he shared that with me … I was counting my coins … young and oblivious … when a dragon slunk out from the hole and would have burned me alive if Bastophon had not … pushed me … and burned in my place … I ran away … looked over my shoulder just once and I saw the woman, still there … gathering Bastophon’s bones …”

Krassios’ face was haunted

“She has whispered in my dreams ever since,” he said, “I know the sound of her voice, the flapping of her wings. It was her that ushered me to the black lyre …”

“Who is she?” asked Ida, her voice barely a whisper.

Krassios shook his head.

“Go,” he said, “If she is here, you must leave Athens, quick as you can. If you don’t, then bring a spoon for your last earthly meal, for by high noon tomorrow, I will be vulgar-tortoise soup, and all Athens will die.”

The massive, bronze cauldron sat atop a mound of kindling at the center of the agora. An immense crowd had gathered there to see the Vulgar Tortoise finally suffer for his many improprieties. Yet Krassios did not whimper when he saw the fire lit or when the water began to bubble and froth. He just told his handlers bawdy limericks, and they tried their hardest not to laugh.

Somewhere amongst the throng stood Hubricretes, who could not keep from fussing with the stubborn black lyre. His sister had been seen fleeing through the Dipylon gate that morning with only her tears and her instrument. Now the man who had mocked him was about to die. He wanted to play something triumphant to celebrate, but the damned lyre had refused to make a peep since its earth-cracking screech two days before.

At high noon, the prisoner was led up makeshift wooden steps to his scalding doom. The water in the cauldron hissed and popped. As Krassios prepared to step inside it, Eris, unseen by mortal eyes, whispered to the black lyre in Hubricretes’ arms:

“O, Bastophon, thou unfortunate half-god, is that not your old lover there on the precipice of agony and death? Will your blackened bones, still infused with awesome power, stay so silent as this city mutilates his flesh?”

An invisible hand suddenly began strumming the strings on the black lyre louder than any time before; their notes screaming brutal vengeance and volcanic rage, percussive and discordant.

Olive trees round the temple to Athena pulled themselves up by their roots and with gnarled, silver-green branches thrashed and impaled all who stood in their path. Marble statues marched down the Acropolis, drawing torrents of blood with their long, golden spears. The very walls and buildings of the city shook off their foundations and crushed multitudes of warm, fleshy bodies into warm, bloody paste while Gaia cracked open her jaws and swallowed innumerable others.

Athens held its bleeding ears and screamed. Her people ran amok; free-men and slaves, nobles and beggars, women and livestock, rhetors and sophists. Death did not bother with castes.

Hubricretes threw his black lyre to the ground, but invisible fingers kept plucking the strings. And as he turned to run, the boiling water within the cauldron twirled up into the air like a terrible dragon. It swooped down upon him and carried him up to the sky, where it melted his flesh from his bones.

In the quiet stillness that eventually followed, Krassios alone would limp away from that city of smoking rubble, looking back only once to see a dark, winged figure gathering bones from the ruins while she hummed a familiar tune ….

END

[Cardigan Broadmoor is a writer from Rhode Island, the state that gave us H. P. Lovecraft, the vampire Mercy Brown, and weiners & coffee milk. His work (alternately described as disturbing and bizarre) has previously been published by Hellbound Books, Black Hare Press, and the Weird Christmas Podcast. He can currently be found on Facebook and Instagram.]