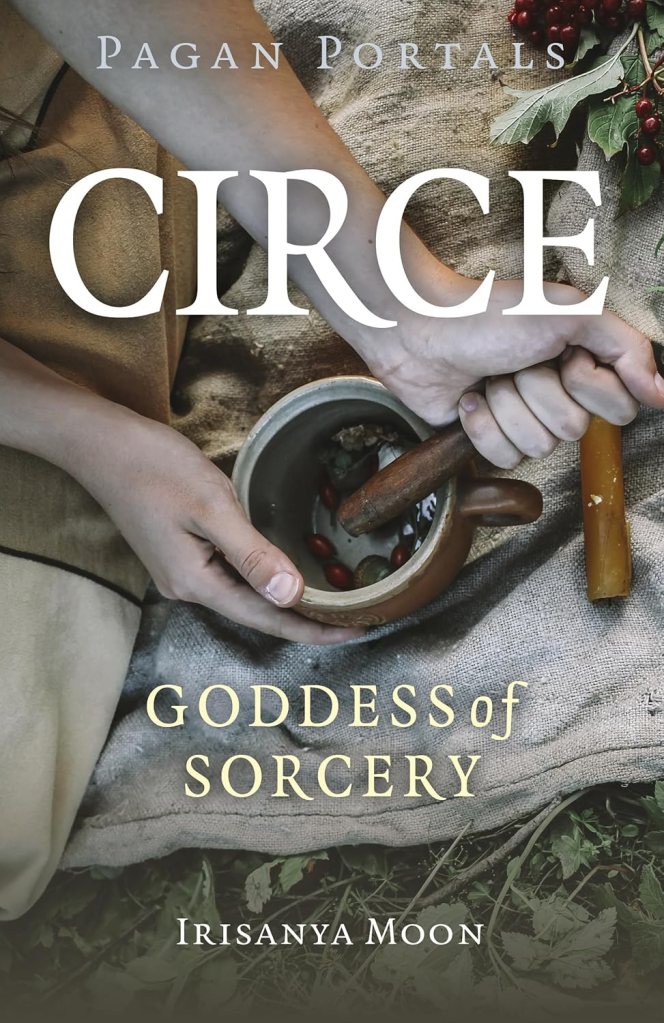

Title: Pagan Portals: Circe — Goddess of Sorcery

Publisher: Moon Books

Author: Irisanya Moon

Pages: 88pp

In Circe: Goddess of Sorcery, Irisanya Moon offers a complex portrait of the classical Homeric witch. Beginning with an overview of Circe’s birth and background — daughter of Helios, the sun god, and Perse, a nymph born of Oceanus — the book provides excerpts from stories and myths in which Circe appears. The literary sources include Homer (The Odyssey), Ovid (Metamorphoses), and Hesiod (Theogony), along with a few lesser known works such as The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius (Jason and Medea) and early romances by Parthenius (the story of Calchus). One caveat Moon offers is the role that translations have played across the centuries in portraying different elements of figures such as Circe. There is, of course, the limitation of language as such, but also the biases inherent in the translators, the majority of whom have been men. The extent to which Circe as any number of other female figures can be justly regarded as “true to form” and objectively portrayed (to recall just the Greeks, think Pandora, Medusa, Arachne, etc.) is a matter that Moon urges the reader to consider through a critical if not skeptical lens.

It is interesting to note, in this connection, that the great Homeric hero, Odysseus, is portrayed early as “a complicated man,” and yet most portrayals of Circe up to the present day touch almost exclusively on the episode of her changing Odysseus’ men into pigs through herbal sorcery. There is also of course the famous image of Circe presenting a cup of poison to Odysseus, immortalized through the Waterhouse painting. Beyond these archetypal scenes, however, Circe tends not to reach the world as a particularly “complicated” woman. She presents as a kind of cruel sorceress and as a figure to be feared, and ideally avoided. Odysseus prevails over Circe’s charms ultimately because he is favored by the gods (he eludes the same fate of his men only with a little help from his good pal Hermes). Moon’s book, however, presents a more complicated and diverse portrait of Circe — even in a passage from Homer excerpted we find “Kirke (Circe), a goddess with braided hair, with human speech and with strange powers” (14). Reading this passage alone, the reader is brought to regard Circe in a more nuanced, humanized light.

Beyond the background matter and the more complex character portrayal, Circe emerges in this book ultimately as a deity with whom one can forge a relationship to advance one’s own spiritual development and magical practice. Honoring the magical gifts of Circe and transmuting emotion into action is a way towards empowerment, as Moon writes, “to call the power back to you” (44). With chapters on spellwork and necromancy, Moon offers meditative strategies for working with this complex and cunning goddess of sorcery, this “most beautiful and most dangerous witch,” as the great Greek scholar, and translator, Edith Hamilton describes her (see Hamilton’s Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes). The book is very much intended not as a single source compendium, but as a starting point for deeper devotional and magical practice.

Circe: Goddess of Sorcery is a portal into power — the power of magic, the power of spellcraft, the power of myth, and above all the power of restoring to oneself a sense of the eternal divine. Circe holds great power to aid the reader, as she did for Odysseus, in the quest of advancing in the direction of becoming one’s better self. Circe “does not hesitate. She knows what to do next, how to do it, and when to step in. She is a lover, and She loves, She is a healer and a hexer. She is a force to be reckoned with and Circe can teach you about power” (79). It’s best, I suspect to keep on Her better side.

In the end, then, I do recommend the book. Circe could be read alone or, better, as a companion book to Artemis: Goddess of the Wild Hunt & Sovereign Heart, also by Irisanya Moon. Both of these books in the Pagan Portals series present a more complex portrait of these Greek goddesses who, incidentally, share one fascinating feature: probable origins in the Minoan pantheon. This is a tantalizing detail and one that has set this reader, at least, on a hunt to discover the connection, be it found or fantastic.

[Reviewed by Christopher Greiner.]