Introduction

I was ten years old the first time I realized that we choose our gods.

Tucked away in ancient Mesopotamia — that cradle of civilization stretching along the Tigris and Euphrates where humans first dreamed of cities around 4000 BCE — lived two sister goddesses whose relationship tells us everything about what we value and what we fear.

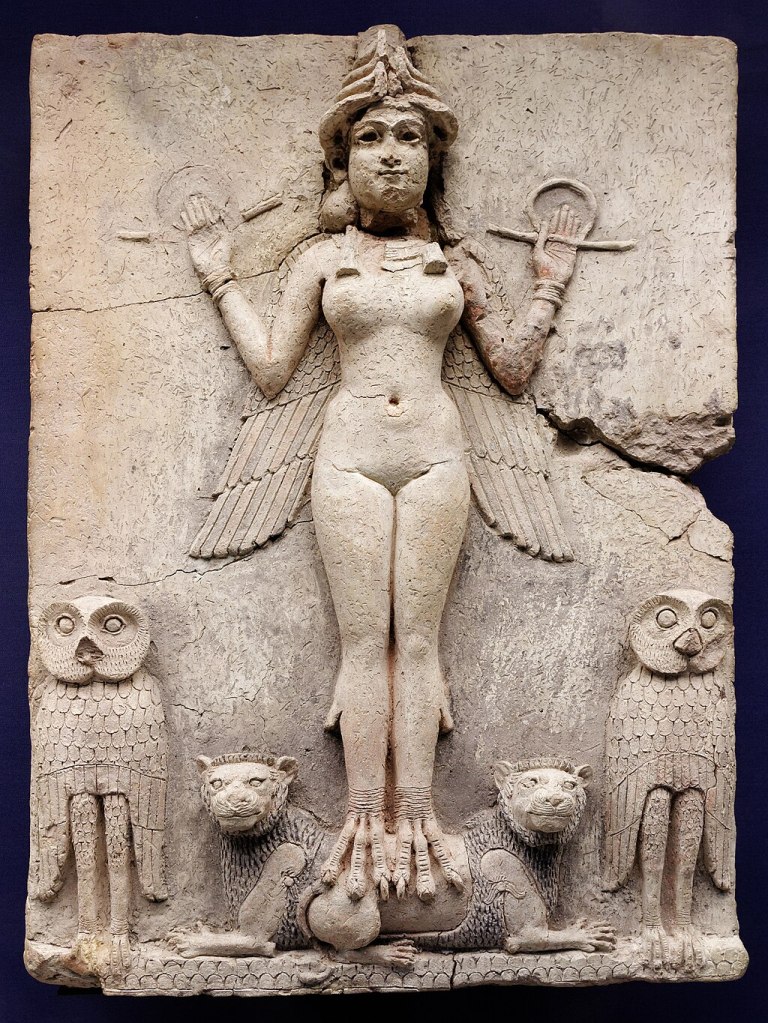

You probably know Inanna, even if you don’t recognize her name. The Queen of Heaven, the Morning Star, later Ishtar to the Babylonians. She’s the one we keep telling stories about — the goddess of love and war, fertility and political power. Her temples crowned ziggurats where kings sought legitimacy. Her descent to the underworld and resurrection became the template for so many stories that followed. We modern folks love Inanna because, well, she represents all the things we’re comfortable celebrating: sexuality, abundance, triumph, rebirth.

But what about her sister? What about Ereshkigal — the Queen of the Great Below — the ruler of the dusty realm called Kur or Irkalla in Mesopoptamian cosmology? Archaeologists have uncovered countless hymns to Inanna, but Ereshkigal is largely relegated in academic footnotes. It’s not just archaeological accident — it’s our collective discomfort with what she represents.

Death. Ending. Necessary darkness.

When we interface with these ancient stories, I’m very aware of how little we’ve really changed. We still crowd around altars to abundance and avoid the temples of completion. We celebrate beginnings but shield our eyes from endings. Yet the Mesopotamians understood something we’ve forgotten: the cosmic dance requires both sisters. There is no creation without dissolution, no birth without death, no light without shadow.

I wonder what might change if we honored both sisters equally? What wisdom might we discover if we approached Ereshkigal not with fear but with reverence for her necessary work? What parts of ourselves might we reclaim if we acknowledged that descent is as sacred as ascent?

Let’s journey together into the Great Below, where a queen too long ignored awaits with truths we desperately need to remember.

Hymn to Ereshkigal

Queen of seven gates, I name you not lightly.

The dust of your realm collects under my fingernails,

inevitable as sunrise, as death.

You who hold the me* of the great below,

you who received no invitation but claimed

your sovereignty regardless —

I do not bring you flowers. I bring you

the knowledge of flowers: how they rot,

how they feed what comes after.

In the houses of the living, they speak

your sister’s name more freely. As if light

were the only worthy kingdom.

But I have seen how shadows define the shape of things.

How endings consecrate beginnings.

How silence holds wisdom noise cannot touch.

When I bend to the earth, when I taste soil,

I am rehearsing for you, Ereshkigal.

Not in fear but recognition.

The scales of justice hang in your hall.

You who are not cruel but necessary,

not vengeful but unflinching.

Where others turn away, you witness.

Where others negotiate, you state the price plainly:

everything returns to you eventually.

In my marrow, in the hollow spaces between heartbeats,

in the moment before dawn when the world seems

both utterly silent and full of invisible motion —

I sense your realm pressing against the membrane of the living.

Not as threat but as promise: nothing is truly lost,

only transformed under your obsidian gaze.

Lady of the Great Earth, keeper of what endures,

accept these words as offering.

I acknowledge your throne of lapis darkness.

I honor the fertility of endings.

I bow to the queen who needs no permission

to claim her rightful domain.

When my time comes to descend your seven steps,

may I do so with the dignity of one who did not

turn away from your truth while living.

Ereshkigal, Sovereign of Depths,

your realm is not absence but fullness beyond bearing.

Not punishment but completion.

I speak your name with the respect owed to necessity.

I leave this offering at the threshold between worlds:

my recognition, my reverence, my return.

*The word “me” (pronounced “may”) in Sumerian mythology refers to divine powers, attributes, or decrees that govern different aspects of civilization and the cosmos. These “me” were considered the fundamental elements that allowed the universe to function properly — almost like divine algorithms or cosmic laws. They represented divine authority and knowledge over a particular domain.

[Stephen Jackson is a writer, musician, and educator living on the border between the United States and Mexico. His work frequently explores the liminality of spaces, systems of belief, and interactions between the sacred and secular. Past works have been published in “Black Fox Literary Journal”, “Miserere Review”, “The International Human Rights Art Movement Literary Journal”, and anthologized in the collections “Bayou, Blues and Red Clay”, “Dawn Horizons”, and “Ghosts Echoes and Shadows”. His first book of short stories, “Spring Variations” was published in February 2025. ]