Publius Cornelius Tacitus was a major Roman historian who lived from about 55 to about 120 C. E. Among other claims to fame, he is the first to give us information about Germanic songs. Tacitus introduces his discussion about the origin of the Germanic peoples by telling us that “celebrant carminibus antiquis [..] Tuistonem deum terra editum” (Tacitus 1988:70) (They celebrate Tuisto, a god produced by the Earth, in ancient songs). The name of Tuisto’s son Mannus is related to such words as English man, Swedish man, and Gothic manna, as well as to Sanskrit mánu- (Svenska Akademien 1942:164). Tacitus is very interested in the content of the Germans’ songs because he states that these are the only means by which they have recorded their history.

In the early sixth century C. E. the Gothic historian Jordanes wrote in his Latin history of the Goths, Getica, about the Gothic songs recounting the military victories of their ancestors (Макаев 1976:33). These songs were accompanied by a cithara, which in Latin refers to a stringed instrument, typically a lyre. Similarly, in the early seventh century, the encyclopedist Isidore writing in Spain stated that the Goths there sung songs about the deeds of their ancestors, to the accompaniment of a cithara. The Russian philologist V. N. Toporov pointed out that some of the Goths’ songs may have dealt with mythological themes just like Tacitus’ account of the Germanic songs featuring the earthborn god Tuisto (Топоров 1983:251).

Among the Proto-Germanic loan words in the modern Finnish language is kulta (gold) from Proto-Germanic *gulꝥa- (Seip 1955:7). (The asterisk means that the word has been reconstructed by linguists instead of being attested in written records.) This seems to imply that at least some of the Proto-Germanic speakers were engaging in trade that included gold with some of the earliest pre-Finnish speakers. It comes as no surprise that the associated Proto-Germanic word *χrenga (ring) – which has left such descendants as German Ring, Old Icelandic hringr and Swedish ring – was borrowed to give modern Finnish rengas (Pipping 1922:97). Of course, this does not prove that either the Germanic or the Finnic peoples were necessarily mining gold at the time. In fact, Tacitus specifically states that the Germans mined neither gold nor silver. He also states that this does not prove that gold and silver deposits are absent in Germany, since no one had searched for these minerals there (Tacitus 1988:72). Consistent with Tacitus’ account, the gold in question could well have come from the Romans. After all, he does tell us that the Germans who lived near the Romans obtained gold and silver in trade with them and came to value these metals (Tacitus 1988:74). This process seems to have gone on for centuries. A curious remnant of this is the name of the traditional smallest unit of Swedish currency, the öre, which was borrowed into Proto-Norse from Latin aureus, a word which originally meant ‘golden’ (Wennström 1926:136).

Proto-Germanic speakers were not the only Indo-Europeans with whom the Finnic peoples had direct contact in Tacitus’ time. In line with Tacitus’ evidence of contact between the Fenni and the Slavonic Veneti, it is reasonable to expect some exchange of vocabulary there as well. An instance is the Proto-Slavonic word which turns up in Old Russian as орь (horse). This corresponds to modern Finnish ori and Karelian orih (horse) (Попов 1964:247).

Tacitus refers to Germanic worship of the Egyptian goddess Isis (Tacitus 1988:76), which seems to testify to cultural contact with Egypt already before the Roman occupation of part of Germany. But neither this early contact, nor the later spread of Egyptian religion, particularly the worship of Isis, in Roman Germany has left clear traces of the Egyptian language in the vocabulary of Germanic languages such as English. There is every chance that the main language of the Egyptian devotees of Isis involved in the spread of her worship was Greek.

By this time the Egyptian language itself was changing under the influence of Greek, even coming to be written in a version of the Greek alphabet. This late stage of Egyptian is normally referred to as Coptic. With the Christianization of Egypt, the Bible was translated into Coptic, and the study of the Coptic Bible often involved considerable study of Greek Bible terminology (Torallas Tovar 2013:111). Even Coptic writings from a Christian milieu may sometimes have interesting things to say about paganism, such as a reference to pagan idols of silver and gold (Ернштедт 1986:193).

A great deal of Egyptian knowledge formulated in the Greek language continued to influence Europe, including Germanic cultures, long after the conquest of both Egypt and parts of Germany by the Romans. For example, material from the second century CE Damigeron-Evax work on what were believed to be therapeutic properties of gemstones was incorporated into Bishop Marbode of Rennes’ late eleventh century CE Latin work De Lapidibus. This was in its turn translated into Old Icelandic around 1200 CE (Kreager 2022:121).

Let’s look a bit further.

The nineteenth-century German historian Friedrich Christoph Schlosser translated and discussed what the Greek writer Agatharchidas – also often spelt as Agatharchides – had to say about gold mining in Ptolemaic Egypt. This includes an account of how female slaves worked at the mills under appalling conditions grinding auriferous rock material in order to extract gold from it (Schlosser 1828:183). This work by Agatharchidas has also attracted the attention of a number of later researchers including William Jacob and Karl Marx (Marx 1983:215). In recent years French archeologists have been excavating the gold mining areas in question and have correlated physical evidence with details of Agatharchidas’ written account (Redon 2025).

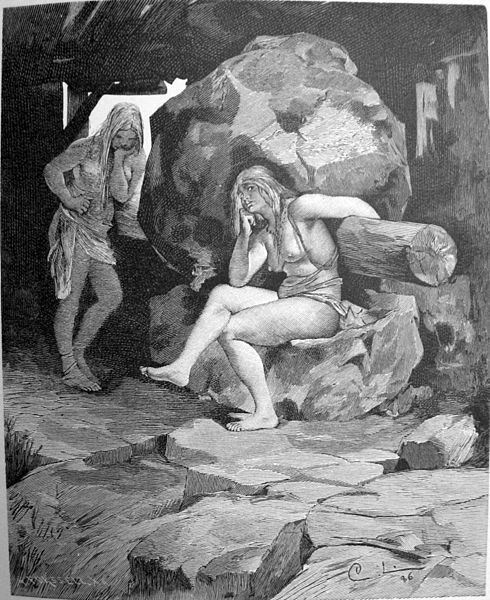

Moving forward over two millennia, we find that in modern Swedish the word Grottekvarn may be used, a bit like English rat race, to refer to the profit-driven relentless pace of work in modern industrial society. Its modern use stems from the song Den nya Grottesången (The new song of Grotte), published by Viktor Rydberg in 1891. This song alludes directly to the mill named Grotte with which, according to Old Norse stories and with specific allusion to the Old Icelandic poem Grottasöngr, King Frode had his female slaves mill gold (Svenska Akademien 1929:973). In Grottasöngr the slaves are two giantesses named Fenja and Menja who grind gold for the Danish king Fróði (Vésteinn Ólason 2005:116). A heartening feature of the Norse story is that the two giantess slaves rebelled against their royal owner and killed him. Good riddance to Fróði. Forward, giantesses! This explains some of the song’s appeal to modern socialists.

In Old Norse, Grotti is the name of the mill without any other clear associations. This is normal enough for a proper noun, since the prototypical proper name does not tell us anything about its bearer other than that it has that name (Andersson 2000:118). Rydberg’s song is big on emphasizing the power of gold. His song is a curious piece of work which also features things like a mosaic made of gold and jasper (Rydberg 1899:210) and the use of basalt and gold in the construction of a temple (Rydberg 1899:213). The “canonical” version of Grottasöngr in Old Icelandic may have been composed as late as 1200 CE by a Christian poet (Vésteinn Ólason 2005:132), but there is no doubt that other versions of the story were circulating much earlier. I am struck by the fact that one of the most important sources of information about the song, the Old Icelandic Edda by the thirteenth century historian and poet Snorri Sturluson, states that Fróði ruled Denmark at the same time as Augustus ruled the Roman Empire (Guðni Jónsson 1945:176). It was none other than Augustus who conquered Ptolemaic Egypt and incorporated it into the Roman Empire.

The theme of the female slaves grinding out gold seems to have come to the Germanic peoples – along with Roman gold mined in Egypt – in early Roman Imperial times and to have served as the basis for its inclusion in Nordic poetry and songs over centuries. This was well before that kind of gold mining and rock processing took place on Germanic or Finnic territory. Transmission to the early Finnic peoples would explain the presence of the coveted Sampo in the Finnish epic Kalevala. It is not quite clear what the Sampo actually was but it is often regarded as having been a kind of mill for grinding out riches, which seems very similar to the Norse mill Grotti. Consistent with this kind of cultural influence, the Finnish word runo (song) was borrowed from Proto-Germanic *rūnō, which is still found in modern Germanic languages such as English rune and Swedish runa (Hellquist 1980:852). As well as having been a song title for the Swedish band Kultivator, there is even a modern Swedish rock band called Grottekvarnen which we can view on the internet.

REFERENCES:

Andersson, E. et al. 2000 Svenska Akademiens grammatik 2 Ord (Svenska Akademien, Stockholm)

Guðni Jónsson (búið hefir til prentunar) 1945 Edda Snorra Sturlusonar með Skáldatali (Bókaverzlun Sigurðar Kristjánssonar, Reykjavík)

Hellquist, E. 1980 Svensk etymologisk ordbok (Andra bandet) (LiberLäromedel, Lund)

Kreager, A. 2022 Lapidaries and lyfsteinar: Health, Enhancement and Human-Lithic Relations in Medieval Iceland pp. 115-155 in: Gísli Sigurðsson og Annette Lassen (Ritstjórar) Gripla XXXIII (Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum, Reykjavík)

Marx, K. 1983 Exzerpte aus William Jacob : An Historical Inquiry into the Production and Consumption of the Precious Metals. Pp. 214-219 In: Marx, K. & Engels, F. Gesamtausgabe (MEGA). Vierte Abteilung. Exzerpte Notizen Marginalien. Band 7. Exzerpte und Notizen September 1849 bis Februar 1851. (Dietz Verlag, Berlin)

Pipping, H. 1922 Inledning till studiet av de nordiska språkens ljudlära (Söderström & Co Förlagsaktiebolag, Helsingfors)

Redon, B. 2025 Iron shackles from the Ptolemaic gold mines of Ghozza (Egypt, Eastern Desert) Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 March 2025

Rydberg, V. 1899 Skrifter af Viktor Rydberg (I) Dikter (Albert Bonniers Förlag, Stockholm)

Schlosser, F. C. 1828 Universalhistorische Uebersicht der Geschichte der alten Welt und ihrer Cultur Zweyten Theils 1te Abtheilung (Franz Varrentrapp, Frankfurt am Main)

Seip, D. A. 1955 Norsk språkhistorie til omkring 1370 (Forlagt av H. Aschehoug & Co. (W. Nygaard), Oslo)

Svenska Akademien 1929 Ordbok över svenska språket (Tionde bandet) (A.-B. Ph. Lindstedts Univ.-Bokhandel, Lund)

Svenska Akademien 1942 Ordbok över svenska språket (Sextonde bandet) (A.-B. Ph. Lindstedts Univ.-Bokhandel, Lund)

Tacitus, P. Cornelius 1988 Germania Interpretiert, herausgegeben, übertragen, kommentiert und mit einer Bibliographie versehen von Allan A. Lund (Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg)

Torallas Tovar, S. 2013 What is Greek and what is Coptic? School Texts as a window into the perception of Greek loanwords in Coptic pp. 109-119 in: Feder, F. und Lohwasser, A. Ägypten und sein Umfeld in der Spätantike Vom Regierungsantritt Diokletians 284/285 bis zur arabischen Eroberung des Vorderen Orients um 635-646 Akten der Tagung vom 7.-9. 7. 2011 in Münster (Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden)

Vésteinn Ólason 2005 Grottasöngur pp. 115-135 in: Gísli Sigurðsson et al. (Ritstjórar) Gripla XVI (Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi, Reykjavík)

Wennström, T. 1926 Ur Svenska språkets hävder. Huvuddragen av vårt modersmåls historia (Bokförlaget Natur och Kultur, Stockholm)

Ернштедт, П. В. 1986 Типология предложения pp. 181-336 in: Ернштедт, П. В. Исследования по грамматике коптского языка (Главная редакция восточной литературы издательства “Наука”, Москва)

Макаев, Э. А. 1976 Рунический и готский pp. 29-41 in: Ярцева, В. Н. (Ответственный редактор) Типология германских литературных языков (Издательство “Наука”, Москва)

Попов, А. И. 1964 Ф. П. Филин, “Образование языка восточных славян” pp. 244-251 in: Білодід, І. К. et al. (Редакційна колегія) Дослідження з української та російської мов (Видавництво “Наукова думка”, Київ)

Топоров, В. Н. 1983 Древние германцы в Причерноморье: результаты и перспективы pp. 227-263 in: Иванов, В. В. (Ответственный редактор) Балто-славянские исследования 1982 (Издательство “Наука”, Москва)

[Dr. Neile Kirk’s most recent publications have appeared in Aothen, Eternal Haunted Summer and NewMyths.]